This is one of the short stories from DEATH AND THE DEVIL, which will be published in ebook format in the next week or two. The theme strikes me as appropriate for Good Friday.

It is a well-established fact across most of the known multiverse that death is, generally speaking, the end of life. This is the sort of obvious statement that most beings understand intuitively, in the same way they understand that water is wet or that the line of traffic you’re not driving in will always move faster than the one you selected.

What is less well established, and indeed known to only a select few cosmic entities, is that there are occasional exceptions to this rule. Not many, mind you—perhaps ten or twelve across the entirety of existence. But when they do occur, they tend to cause no end of paperwork.

Death was having what, for him, amounted to a moderately busy Friday. The Romans were at it again with their crucifixions, and while Death understood the practical necessity of his role in the great cosmic machinery, he couldn’t help but find the Romans’ enthusiasm for creatively prolonging the process somewhat trying. Crucifixion was particularly bothersome—it was slow, messy, and sometimes required him to hover about for hours waiting for the final moment to arrive. It was inefficient, and if there was one thing Death disliked, it was inefficiency.

Outside the walls of Jerusalem, on a small hill that locals called “The Place of the Skull” (humans did have a flair for the dramatic that Death could almost appreciate), three crosses stood starkly against the bright morning sky. A sizeable crowd had gathered—some jeering, some weeping, some simply watching with the detached curiosity of those who have nothing better to do with their afternoon than observe the suffering of others.

Death materialized beside the center cross, his black robe somehow remaining pristine despite the dust that swirled across the hilltop. His scythe gleamed with an impossible light, as if it were reflecting stars that weren’t visible in the daytime sky.

I AM EARLY, Death said, his voice not so much heard as felt, like the final note of a funeral dirge played on the bones of the universe. He consulted a small hourglass that appeared in his skeletal hand. The sand was still flowing, though it had noticeably thinned to the bottom half. There was time yet.

Death was not alone in his invisible observation of the proceedings. Slightly to his left, luxuriating in the heat that rose from the baked earth, lounged a figure that radiated a different kind of darkness. This darkness wasn’t the simple absence of light that characterized Death’s appearance, but rather a corrupted, oily absence of goodness.

“Lovely day for a crucifixion, isn’t it?” said the Devil, his voice as smooth as expensive honey with just a hint of ground glass mixed in. He wore the shape of a handsome middle-aged man with olive skin and curly black hair, dressed in a toga of deepest crimson that seemed to shift and flow like liquid. Only his eyes—amber with vertical pupils—gave away his inhuman nature.

Death did not respond. He had long ago learned that engaging the Devil in conversation inevitably led to tedious debates about the nature of free will or sales pitches for various soul-collection optimization schemes.

The Devil seemed undeterred by Death’s silence. “Quite the turnout for this one,” he continued, gesturing at the crowd around the central cross. “Special case, you know. I’ve had my eye on him for years. All those irritating miracles, healing the sick, giving sight to the blind.” He made a dismissive gesture. “Bad for business, you know, that sort of thing.”

Death remained silent, watching the sand in the hourglass.

“Oh, come now,” the Devil prodded. “He’s been a thorn in your side too! Remember, he’s the one who interfered with your soul-reaping.”

At this, Death’s eye sockets seemed to narrow slightly, the silver pinpricks of light within them intensifying.

YES, he said finally. I REMEMBER.

The memory was, for Death, quite a vivid one, despite having occurred several years earlier by human reckoning. He had appeared in Bethany to collect the soul of a man who had succumbed to an illness that baffled the local physicians. It had initially been a straightforward collection—Death had appeared at the appointed time, raised his scythe, and completed his duty with his usual efficiency. The soul had been collected, the hourglass emptied, the paperwork filed. End of story.

It should have been, anyhow.

Four days later, Death had received an urgent message from the Department of Post-Mortem Records about an “anomalous post-mortem event.” He had returned to Bethany to find something unprecedented—Lazarus, very much alive, moving about, eating, breathing, and talking, despite having been quite thoroughly dead, reaped, and buried days before.

More perplexing still was the matter of his second hourglass. Every mortal had exactly one hourglass, created at birth and destroyed at death. Lazarus’s hourglass had been properly disposed of following the collection of his soul. Yet somehow he was alive again, and he also had a new hourglass in the usual location—but from whence had it come? Who had authorized it? Death checked and rechecked the records, but he could find no indication of how this administrative nightmare had occurred.

And at the center of this troublesome accounting error was the same man who now hung on the central cross.

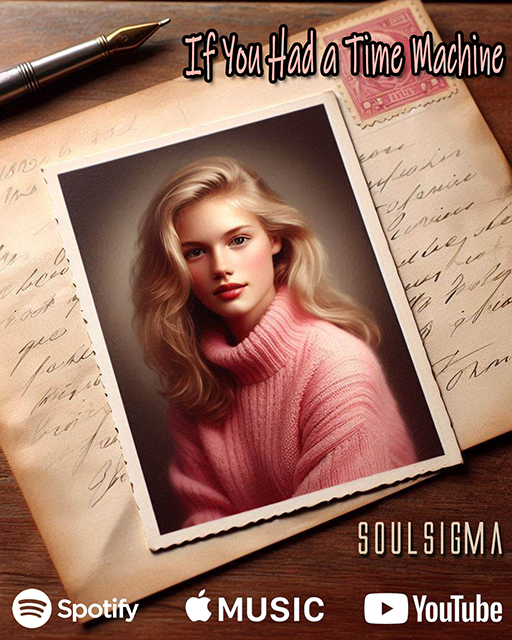

Continue reading “DEATH AND THE PLACE OF THE SKULL”