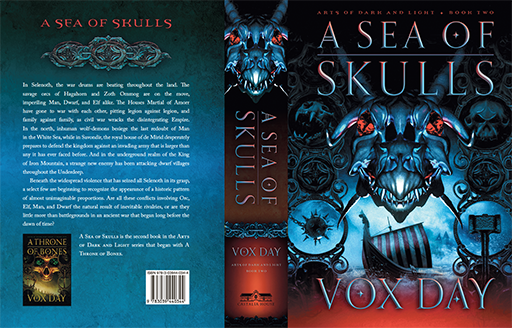

Didact’s Mind wrote a very favorable review of the preliminary edition of A SEA OF SKULLS back in 2017. It would be interesting to know if he feels the completed work holds up to his initial perspective on it.

Vox Day has not merely matched George R. R. Martin’s fantasy writing skills and output. He has exceeded him, by miles, leaving old Rape Rape wheezing and panting in the dust.

In fact, I am willing to go so far as to argue that, with this book, Vox Day has catapulted himself into the storied and rarefied rank of writers that sits just below The Master himself.

That’s right, I went there. I just said that Vox Day has written a book that is nearly as good as J. R. R. Tolkien’s work.

Not as good. But not terribly far off, either.

From one fantasy fan to another, praise simply does not come any higher than that.

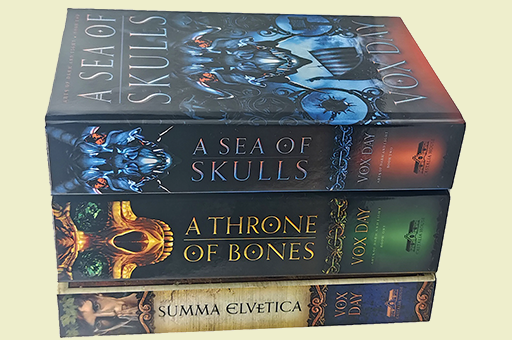

Vox’s accomplishment is made all the more astonishing by the fact that this isn’t even the completed book yet. It’s less than half of the full work. This book is already far more complex, more layered, and simply bigger in scale and scope than its predecessor. There are far more point-of-view characters, the battle sequences are way bigger, the size of the world that Vox Day is playing with is far greater…

The result is so good that it deserves to be called the finest high-fantasy book of its time.

Make no mistake: this now puts Vox Day right below The Master himself in terms of writing- right up there with C. S. Lewis, John C. Wright, and maybe two or three others. And that is an astonishing achievement, given that neither Tolkien nor Vox can rightly be considered first-rate fantasy writers.

One of the interesting things about the comparison between Tolkien and Day is that neither of them are really writers to begin with. Vox Day started out as a musician and a game designer. Vox himself will readily admit that his writing is not as good as Tolkien’s- because it isn’t. Yet Tolkien was a linguist, whose strong Christian faith and interest in Scandinavian mythology helped him create a fantasy world. The reason both Tolkien and Day succeeded, where so many dedicated professional authors would have failed, is because they focused on their respective strengths and wrote works of epic fantasy that played to them…

This book is, quite simply, an extraordinary achievement. With it, Vox has separated himself from all of his contemporary rivals and has clearly laid down a marker for everyone else to match- and I personally don’t think anyone will be able to do so for years, maybe decades, to come.

It’s entirely up to the reader to see if the most recent volume in ARTS OF DARK AND LIGHT holds up to the promise of its earlier and abbreviated release. But for my part, what I will say is that one reason it took me so long to complete the book and get it out is that I was determined to at least try to deliver something that was consistently at the same level as A THRONE OF BONES. I took PG Wodehouse as my inspiration here, as his work is remarkably consistent throughout a novel; he was quite purposeful in attempting to ensure that every scene and every page stood up well on its own. This required a significant amount of discipline in not permitting the story to expand willy-nilly in any direction that happened to capture my attention at the time.

As we’ve seen from George Martin’s failure to finish his epic fantasy, while it’s much easier to churn out words by following one’s momentary whims and exploring whatever tangent happens to strike one’s fancy, this inevitably leads to a wider scope and excessive perspective characters that will, sooner or later, render the story too large to write. One of the many geniuses of JRR Tolkien was his ability to keep his epic story tied very tightly to a fairly small number of key characters, keeping them in physical proximity to each other, and thereby preventing the story from continually expanding to the point that it escaped his ability to reasonably describe it.

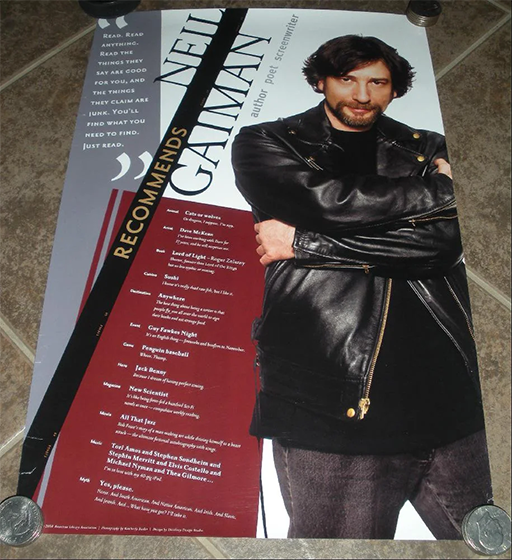

Only time will tell, but in A SEA OF SKULLS, I believe that I successfully conquered the challenge of the middle book, which in any trilogy is always the hardest book to write because it has to expand upon the first book without exploding in a manner that renders closure in the third book impossible. It’s interesting that one seldom hears writers discussing these technical matters, but this is probably because the sort of writers who attend workshops mostly write short stories, while the writers who teach them are either self-promoters like John Scalzi or successful mediocrities cruising for starstruck young women like Neil Gaiman, neither one of whom could write epic fantasy if they tried.

Anyhow, for better or for worse, it’s done now and I’m on to the final volume in the series. If Didact’s Mind updates his review, I’ll be sure to post a link to it here.