You know a book is good if your wife keeps asking what you’re laughing at. The answer was this book. It is funny, it is really funny. And the ending will leave a tear in your eye.

“What’s so funny there?”

she whispers through the lamplight

as he grins and reads

You’ll understand the haiku if you read the book.

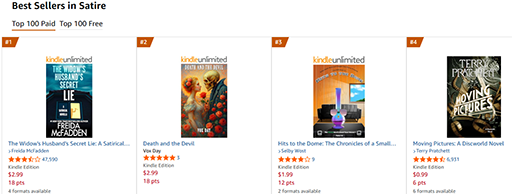

A review of DEATH AND THE DEVIL.

DEATH AND THE DARWINIAN

It is a well-established fact across most of the known multiverse that death is, generally speaking, the end of life. This is the sort of obvious statement that most beings understand intuitively, in the same way they understand that water is wet or that the likelihood of autocorrect humiliating you increases exponentially with the importance of the message being sent.

What is rather less well-established is what happens immediately after death, in that awkward period between the cessation of biological functions and whatever comes next. This is primarily because most beings who experience death are, by definition, no longer in a position to write detailed reports about it, and those who claim to have had “near-death experiences” typically experience something more akin to “near-near-death” or “death-adjacent” moments, which is rather like claiming to be an expert on the history of Paris because your plane once flew over the south of France.

Dr. Mortimer Finch, professor of evolutionary biology at the prestigious University of West Anglia, had spent his entire fifty-seven-year academic career insisting that death was merely the natural conclusion of a biological process, a physical event no more spiritually significant than the shedding of a snake skin or the molting of an upwardly mobile crab. The universe, Dr. Finch maintained, was a magnificent accident—an unplanned, undirected series of chemical and physical processes that, through billions of years of trial and error, had produced everything from slime molds to symphony orchestras.

This conviction had served him well throughout his distinguished career, earning him numerous academic accolades, a comfortable tenure, and the quiet disdain of the university’s theology department, whose offices were, perhaps not coincidentally, located in the building on the opposite side of the campus.

It was therefore somewhat disconcerting for Dr. Finch to one day find himself face-to-face with Death.

Not with the abstract concept of death about which he had lectured about so confidently to generations of undergraduates. Not with the cessation of metabolic functions, the breakdown of cellular integrity, and the dispersal of organized energy into entropy. No, this was Death with a capital D, complete with a flowing black robe, a gleaming scythe, and a skull that somehow managed to express mild interest despite having no facial muscles whatsoever.

“This is obviously a hallucination,” Dr. Finch declared, adjusting his spectacles out of habit, despite the fact that they were now as spectral as the rest of him. “A final neurochemical discharge as my brain shuts down. Quite fascinating, really.”

Death regarded him with eye sockets that contained tiny silver points of light where eyes might have been expected.

I AM NOT A HALLUCINATION, Death said in a voice that wasn’t so much heard as felt, as if it was the final note of a funeral dirge played on the bones of the universe.

“That’s exactly what a hallucination would say,” Dr. Finch replied with the confident tone of a man who had won numerous academic debates through sheer force of authoritative pronunciation. “My brain, in its oxygen-deprived state, is creating a culturally recognizable figure to help process the fact that I’m dying. You’re a psychological construct, nothing more.”

Death sighed, a sound like a desert wind whistling through ancient tombs. Dr. Finch’s reaction was not an uncommon one. Humans, in particular, had a remarkable capacity for maintaining a state of denial even in the face of overwhelming evidence. It was one of their most distinctive traits, ranking just behind opposable thumbs and just ahead of their inexplicable insistence on keeping pets that were either venomous, temperamental, or both.

YOU ARE ALREADY DEAD, Death clarified, pointing a bony finger at Dr. Finch’s body, which was currently cooling on the laboratory floor beside an overturned stool and a half-eaten tuna sandwich. YOUR HEART STOPPED SEVENTEEN SECONDS AGO. CEREBRAL ACTIVITY CEASED FOURTEEN SECONDS AGO. YOU ARE NOT HALLUCINATING. YOU ARE, BY EVERY SCIENTIFIC DEFINITION, DECEASED.

Dr. Finch glanced at his body with mild interest, as if observing a moderately engaging museum exhibit.

“Cardiac arrest, by the look of it. I always suspected it would be the heart. Too many late nights in the lab, too much caffeine.” He turned back to Death. “But this conversation is still taking place inside my dying mind. I’m talking to myself. This is some sort of complex psychological self-delusion, probably the result of seeing my mother in the bathtub when I was five years old or something like that.”

Death’s patience, which had been cultivated over eons of existence, began to show its first microscopic signs of wear.

DISCUSS ON SG