This should present a good test of the Triveritas and its ability to assess truth claims and how warranted they are. Let’s see how it fairs:

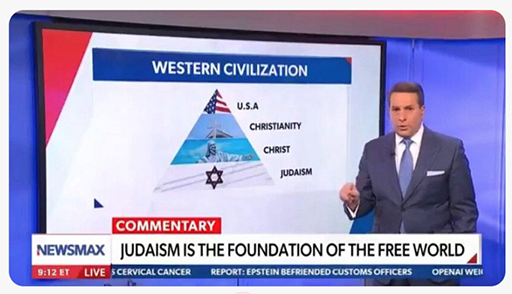

The Claim: Judaism is the foundation of the free world, and the correct foundational structure of Western Civilization is: Judaism -> Christ -> Christianity -> USA.

L: Logical Validity

The claim fails L in at least three distinct ways.

First, it commits an equivocation between Judaism-as-ethnic-religion and Judaism-as-philosophical-system. The religious tradition that produced Christ was the Hebrew religion of the Second Temple, a diverse, internally fractured tradition that included Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, Zealots, and Hellenized diaspora Jews, among others. Modern rabbinical Judaism descends primarily from the Pharisaic tradition and was formalized after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, partly in explicit reaction against Christianity. Claiming that “Judaism” is the foundation of the free world conflates these into a single continuous entity, which is historically and theologically incoherent. The Judaism that exists today explicitly rejected the very element (Christ) that the chain claims it produced. You cannot simultaneously claim credit for the product and reject the product.

Second, the chain omits essential intermediate links. Even if the false theological genealogy were to be granted, the sequence Judaism -> Christ -> Christianity -> USA skips Greece, Rome, the Germanic tribal traditions, English common law, the Magna Carta, the Protestant Reformation, the Enlightenment, and the entire tradition of Anglo-Saxon political philosophy from which the American founding actually derived. The Founders cited Cicero, Locke, Montesquieu, and the English constitutional tradition far more than they cited Moses or the Torah. The logical structure of the chain presents a linear causal sequence while suppressing the majority of the actual causal inputs. This is not a simplification. It is a falsification. A chain that omits the most important links is not a chain. It is a narrative.

Third, it confuses necessary conditions with sufficient conditions and with foundational primacy. Even if Judaism was one of many inputs into the civilizational stream that eventually produced the American republic, being an upstream input does not make you “the foundation.” Water is upstream of hydroelectric power, but we do not call water “the foundation of electricity.” The Tigris and Euphrates are upstream of Western agriculture, but we do not call Mesopotamian irrigation “the foundation of the free world.” The claim takes one thread in a complex tapestry and declares it the entire loom.

L: 9/99 = Fail. Equivocation on “Judaism,” suppression of the majority of actual causal inputs (Greece, Rome, Germanic law, English constitutionalism, the Reformation, the Enlightenment), and confusion of upstream necessary conditions with foundational primacy. Three independent logical defects, any one of which is fatal.

M: Mathematical Coherence

The claim has no quantitative structure to evaluate in a strict sense, but we can apply the Plausibility Check Principle. If Judaism is the foundation of the free world, we should expect some observable correlation between Jewish civilizational influence and the emergence of free societies. The actual pattern runs the other way. The societies where Judaism was the dominant cultural force (ancient Judea, the medieval Jewish communities of Europe) did not produce political freedom in the modern sense. The societies that did produce political freedom (England, the Netherlands, the American colonies) were overwhelmingly Christian and drew primarily on Greco-Roman and Germanic political traditions. The one modern state founded on explicitly Jewish principles, Israel, is a parliamentary democracy, but its political structure derives from British Mandate-era institutions and European political theory, not from the Torah or the Talmud. The empirical distribution of free societies does not cluster around Jewish cultural influence. It clusters around Protestant Christianity and English legal traditions. The claim predicts a pattern that the data does not show.

M: 8/99 = Fail. The predicted correlation between Jewish cultural influence and free societies not only fails to appear but runs in the opposite direction. The plausibility check is near-total failure, with a few points granted because the Old Testament is genuinely one of many upstream inputs into the broader civilizational stream.

E: Empirical Anchoring

The historical record refutes the claim directly. The American Founders did not understand themselves as building on a Jewish foundation. They understood themselves as building on English constitutional traditions, Greco-Roman republican theory, and Protestant Christian moral philosophy. Jefferson, Adams, Madison, and Hamilton left extensive writings on their intellectual influences. Judaism barely appears. The Declaration of Independence invokes “Nature’s God” and “the Laws of Nature,” language drawn from Deist and Enlightenment philosophy, not from Mosaic law. The Constitution contains no reference to Judaism, the Torah, or Mosaic law. The First Amendment explicitly prohibits the establishment of any religion, a principle that would be incoherent if the nation understood itself as founded on a specific religious tradition.

The claim also fails the Applied Triveritas test. Drop to the lowest level of concrete fact. Name the specific Jewish text, institution, or legal principle that the American Founders adopted as foundational. The Ten Commandments? Three of the ten are specifically religious commandments that the First Amendment forbids the government from enforcing. The Mosaic legal code? The Founders explicitly rejected theocratic governance. The prophetic tradition of social justice? This was mediated entirely through Christianity, not through direct engagement with Jewish sources. At every concrete point of contact, the actual mechanism of transmission runs through Christianity, Greece, Rome, or England, not through Judaism directly.

E: 5/99 = Fail. The Founders’ own writings constitute direct, unambiguous evidence against the claim. You cannot score well on empirical anchoring when the primary sources explicitly contradict you. The handful of points reflect the bare fact that the Bible, which includes the Old Testament, was culturally present in the Founding era, but cultural presence is not foundational primacy.

Triveritas Assessment: 7/99 = Propaganda

The claim fails all three dimensions. It is logically incoherent (equivocation, suppressed premises, confusion of necessary and sufficient conditions). It is mathematically incoherent in the plausibility-check sense (the predicted pattern does not match the observed distribution). It is empirically unanchored (the historical record directly contradicts it). Under the Triveritas, the claim does not merit warranted assent.

It has the structure of a claim but none of the substance. It exists to flatter a particular audience by placing them at the root of a civilizational genealogy they did not build. Every element is selected or distorted to serve the narrative rather than to describe what actually happened. The suppression of Greece, Rome, the Germanic traditions, and English constitutionalism is not an oversight. It is the point. The equivocation between the Hebrew religion and rabbinical Judaism is not a minor terminological slip. It is the mechanism by which the claim smuggles its conclusion into its first premise.

A score of 7/99 means the claim has almost no contact with reality on any dimension. It is not a good-faith attempt to describe civilizational history that gets some details wrong. It is a narrative constructed to reach a predetermined conclusion, with the evidence selected and distorted to fit. The Anti-Self-Sealing Principle identifies exactly this structure: a purely narrative system that substitutes storytelling for prediction, interprets all evidence as support, and never exposes itself to falsification by concrete data.

At 7/99, you are not in the territory of “debatable” or “oversimplified but defensible.” You are in the territory of a claim that fails every independent check available.