The Atlantic is not exactly a publication in which I have any trust whatsoever. But it is informative to note that even some of the most-hallowed mainstream media institutions are beginning to attempt to come to grips with the ineluctable fact that the economic order is on the verge of collapsing because the foundational principles upon which it rests have proven to be false.

The Anglo-American system of politics and economics, like any system, rests on certain principles and beliefs. But rather than acting as if these are the best principles, or the ones their societies prefer, Britons and Americans often act as if these were the only possible principles and no one, except in error, could choose any others. Political economics becomes an essentially religious question, subject to the standard drawback of any religion—the failure to understand why people outside the faith might act as they do.

To make this more specific: Today’s Anglo-American world view rests on the shoulders of three men. One is Isaac Newton, the father of modern science. One is Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the father of liberal political theory. (If we want to keep this purely Anglo-American, John Locke can serve in his place.) And one is Adam Smith, the father of laissez-faire economics. From these founding titans come the principles by which advanced society, in the Anglo-American view, is supposed to work. A society is supposed to understand the laws of nature as Newton outlined them. It is supposed to recognize the paramount dignity of the individual, thanks to Rousseau, Locke, and their followers. And it is supposed to recognize that the most prosperous future for the greatest number of people comes from the free workings of the market. So Adam Smith taught, with axioms that were enriched by David Ricardo, Alfred Marshall, and the other giants of neoclassical economics.

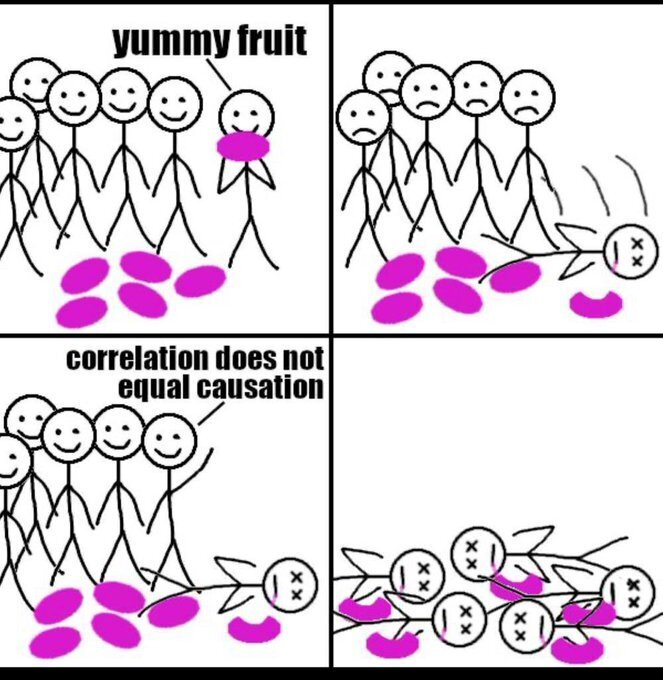

The most important thing about this summary is the moral equivalence of the various principles. Isaac Newton worked in the realm of fundamental science. Without saying so explicitly, today’s British and American economists act as if the economic principles they follow had a similar hard, provable, undebatable basis. If you don’t believe in the laws of physics—actions create reactions, the universe tends toward greater entropy—you are by definition irrational. And so with economics. If you don’t accept the views derived from Adam Smith—that free competition is ultimately best for all participants, that protection and interference are inherently wrong—then you are a flat-earther.

Outside the United States and Britain the matter looks quite different. About science there is no dispute. “Western” physics is the physics of the world. About politics there is more debate: with the rise of Asian economies some Asian political leaders, notably Lee Kuan Yew, of Singapore, and several cautious figures in Japan, have in effect been saying that Rousseau’s political philosophy is not necessarily the world’s philosophy. Societies may work best, Lee and others have said, if they pay less attention to the individual and more to the welfare of the group.

But the difference is largest when it comes to economics. In the non-Anglophone world Adam Smith is merely one of several theorists who had important ideas about organizing economies. In most of East Asia and continental Europe the study of economics is less theoretical than in England and America (which is why English-speakers monopolize Nobel Prizes) and more geared toward solving business problems.

First, Rousseau was always an absurd and nonsensical joke. Second, Steve Keen has mathematically proven the fundamental incorrectness of Adam Smith due to the unreliable nature of the collective demand curve. Third, List is not the solution to Smith, and for the same reason.

The hardest thing for even many of the people on the so-called ideological Right to accept – so-called because Left-Right ideology is incoherent, irrelevant, and entirely outmoded – is that the Enlightenment has proven to be an intellectual and philosophical dead end. Reason, at least in its human embodiment, has turned out to be irrational; all of the models and creeds and policies that rely upon the basic concept of human rationality have not only failed, but have been conclusively proven to be false.

It was simply inertia from Christendom that allowed the Enlightenment to pass itself off as progress. But the systematic eradication of Christianity from intellectual, professional, and public life combined with the adulteration of the European nations is finally overcoming that centuries-old inertia, to disastrous effect.

DISCUSS ON SG