Someone by the name of Joe Bowers has asserted that Probability Zero is “Ignorant and Unscientific Drivel” and offers what he describes as ” a direct, point-by-point rebuttal of the core mathematical claims” in my book. Let’s see how he did:

1. The “MITTENS” mutation accumulation equation

Day argues that the number of mutations required for large-scale evolutionary change exceeds what can realistically fix in a population within available time. The flaw is that he treats evolution as requiring a long chain of specific, pre-targeted mutations that must all occur and fix sequentially. Modern population genetics does not require pre-specified targets. Evolution explores fitness landscapes through branching pathways, neutral networks, standing genetic variation, recombination, and parallel mutations. Multiple mutational paths can lead to similar phenotypes. His math assumes a single narrow path; biology does not.2. Fixation probability simplification

He often reduces fixation probability to approximately 1/N (or similar simplified forms) and then multiplies improbabilities across many required mutations. That approach ignores selection coefficients. The correct approximation for a beneficial mutation is roughly 2s (in diploids under weak selection), not 1/N. Beneficial mutations do not behave like neutral drift events. By modeling them as near-neutral events, he artificially suppresses the rate of adaptive change and inflates improbability.3. Multiplying independent improbabilities

Day multiplies probabilities of sequential mutations as if each required mutation is statistically independent and must occur in a strict order. This is mathematically inappropriate. In real genomes, recombination allows beneficial mutations arising in different individuals to combine. Parallel lineages explore different paths simultaneously. Evolution operates across entire populations, not along a single linear lineage. Treating it like a serial lottery is a category error.4. Effective population size misuse

He frequently uses conservative or arbitrarily low effective population sizes to restrict mutational supply. In reality, many species (especially microbes) have enormous effective populations and rapid generation times, dramatically increasing the number of mutational trials. Even in vertebrates, long time spans combined with standing variation and recombination increase evolutionary capacity beyond what his constrained models assume.5. “Probability zero” threshold claim

He invokes extremely small probability cutoffs to argue practical impossibility. But probability zero in mathematics means literal impossibility under the model — not merely “very small.” His conclusion depends entirely on the assumptions baked into his model. If the model omits recombination, epistasis, neutral networks, regulatory evolution, gene duplication, and exaptation, then the resulting “zero” reflects model incompleteness, not biological impossibility.6. Information increase argument

Day argues that new biological information cannot arise via mutation and selection. This ignores well-documented mechanisms such as gene duplication followed by divergence, horizontal gene transfer, exon shuffling, regulatory evolution, and de novo gene birth from previously noncoding sequences. These processes have been observed and sequenced. The claim that no new information arises is empirically false.7. Large-scale morphological change requirement

He assumes that complex traits require many simultaneous coordinated mutations. Evolutionary developmental biology shows that small regulatory changes can produce large phenotypic effects. Changes in gene expression timing and location often drive macroevolutionary shifts without requiring dozens of simultaneous structural mutations.In short, Probability Zero reaches its conclusion by modeling evolution as a blind, single-threaded, neutral lottery with fixed targets and no recombination. That is not how evolution works. When realistic population genetics, parallel mutation, selection coefficients, and genomic mechanisms are included, the “zero” vanishes — because it was produced by an oversimplified and biologically inaccurate mathematical setup, not by actual evolutionary constraints.

Point 1 claims I treat evolution as requiring “pre-targeted mutations that must all occur and fix sequentially.” This is false. MITTENS counts fixed differences between species—observed genomic divergence documented in the literature. These are not hypothetical, not pre-targeted, and not assumed to follow a single pathway. They are measured. The reviewer is attacking a model I don’t use. The fixed differences between humans and chimpanzees exist regardless of what pathway produced them. The question is whether the mechanism can produce that many fixations in the available time. The reviewer never addresses this, which is the most basic mathematical claim in the book.

Point 2 claims I model beneficial mutations as neutral drift events with fixation probability 1/N. This is the opposite of what I do. The entire MITTENS framework uses Haldane’s cost of natural selection, which assumes selection is operating. The fixation rate limit of one substitution per 300 generations is derived from the selective load—the reproductive excess required to drive an allele to fixation under selection. The 2s approximation the reviewer invokes for fixation probability is irrelevant to the throughput constraint, which is about how many substitutions the population can sustain simultaneously given finite reproductive capacity. The reviewer has confused fixation probability with fixation rate. These are two different things.

Point 3 invokes recombination as a rescue. The Bernoulli Barrier paper addresses this directly and at length. Recombination reshuffles existing variation; it does not accelerate the rate at which any individual allele increases in frequency. Kimura and Ohta (1969) established that expected time to fixation does not depend on recombination rate. The reviewer asserts that recombination is capable of resolving the problem without demonstrating how it changes the mathematics. This is a false and groundless assertion.

Point 4 claims I use “arbitrarily low effective population sizes.” This is totally false. I used published estimates from the population genetics literature. For humans, Ne ≈ 10,000 is the standard figure used by the field itself—it’s not my invention. The reviewer then pivots to microbes, which is irrelevant since the book’s central analysis concerns sexually reproducing organisms. I actually address microbes explicitly because bacteria are the one case where the fixation math works, precisely because they have the features sexual reproducers lack—no recombination delay, complete generational turnover, and astronomical generation counts. The reviewer is citing the exception that was the basis for Kimura’s algebraic error and the subsequent misapplication of his substitution formula.

Point 5 claims Probability Zero reflects “model incompleteness” because I omit recombination, epistasis, neutral networks, regulatory evolution, gene duplication, and exaptation. Each of these is addressed in the book, several of them in complete chapters dedicated to them. The Escape Hatches chapter, the Closing the Escape Hatch paper, and the shadow accounting analysis specifically demonstrate why these various mechanisms do not rescue the model. The reviewer lists them as if simply mentioning them could somehow constitute a rebuttal. It does not. Where is the math showing that gene duplication closes a five-order-of-magnitude shortfall? It doesn’t exist because it can’t do it.

Point 6 claims I argue “no new information arises.” I never made any such argument. Nothing like this ever appears in the book. The reviewer is attacking a position I do not hold and have never even considered. What I demonstrate is that the rate at which fixation can occur is insufficient to account for observed divergence. This is a quantitative constraint, not a claim about the impossibility of mutation producing changes.

Point 7 invokes evo-devo and regulatory changes producing large phenotypic effects. The Closing the Escape Hatch paper addresses this explicitly under shadow accounting: regulatory changes are themselves substitutions. Transcription factor binding sites turn over. Enhancers diverge. Chromatin architecture evolves. These are all fixations that must be accounted for. Calling them “regulatory” rather than “structural” does not exempt them from the fixation throughput constraint. The accounting still applies.

The summary paragraph is the evidence that the reviewer hasn’t even read the book. The reviewer describes the Probability Zero model as “a blind, single-threaded, neutral lottery with fixed targets and no recombination.” This bears no resemblance to anything in the book. It is a straw man constructed from standard anti-creationist talking points, it’s not a criticism of the actual text. The reviewer has written a review of a very different book by listing standard objections to arguments I never made.

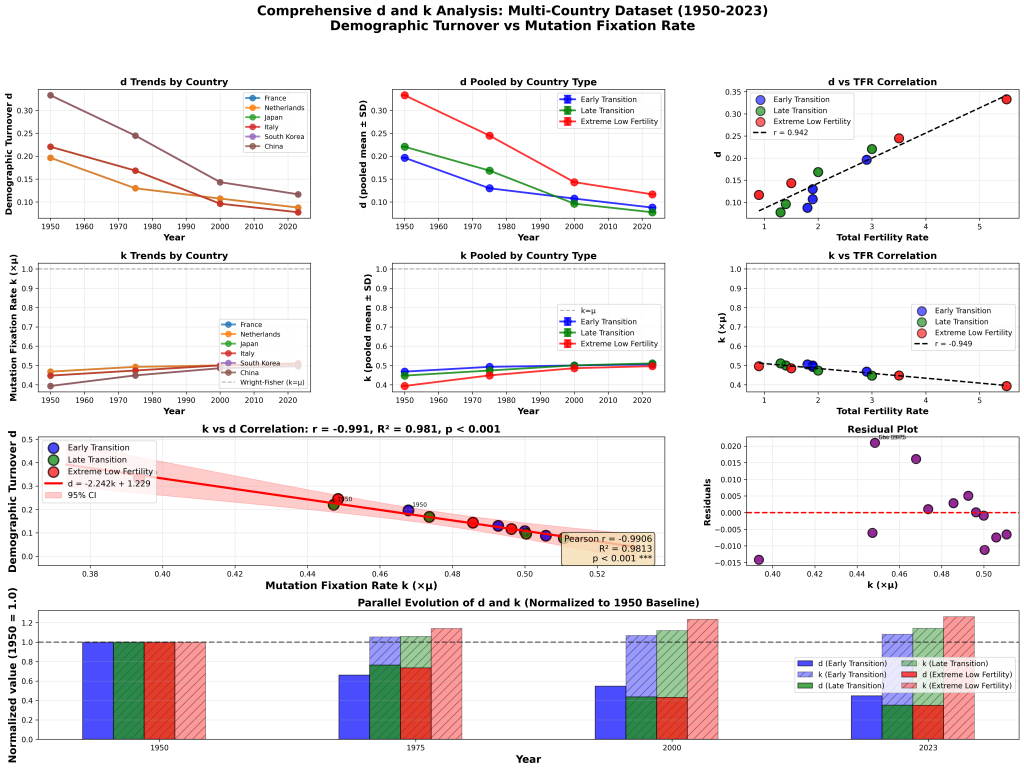

Every point is either addressed in the text, is based on a misreading of the argument, or is an assertion offered without mathematics. Not a single calculation. Not a single specific engagement with any of my actual numbers. The reviewer never mentions the 220,000× shortfall, never addresses Haldane’s cost, never engages with the Bio-Cycle model or the d coefficient, never mentions the ancient DNA validation data. Seven points, zero math, zero engagement with the actual argument.

It’s not a review or a rebuttal, it’s not even a critique. It’s just a midwit attacking a figment of his own imagination.