A few things. First, I’ve got two related posts up at White Bull that may be of interest to those who are either a) trying to break into a new industry or b) interested in the history of the game industry. I used my own experience of going from a complete outsider to an industry oldtimer as a practical example; the first post is here and contains a link to the second one at the end.

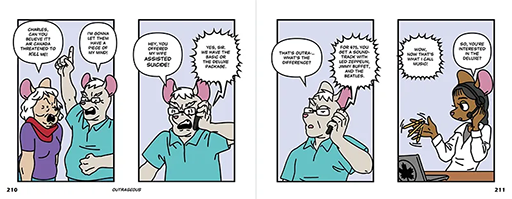

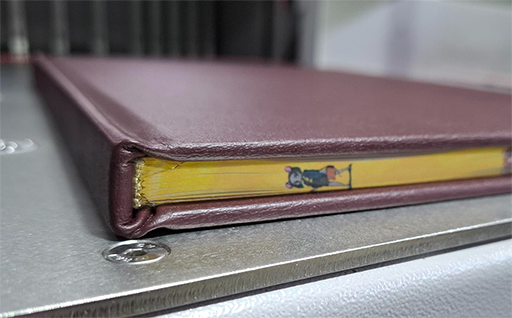

Second, if you’d like to see what the very large and very pretty Hypergamouse hardcover looks like, there are some pictures up at Sigma Game. The pictures and a video will go up on Arkhaven later. And speaking of Arkhaven, the Dark Herald has a detailed discussion of one of my favorite books by Tanith Lee, Delusion’s Master, that is well worth reading by anyone who enjoys the dark side of fantasy.

Third, we’ve opened up the SOULSIGMA campaign again for the nine backers whose backings didn’t go through due to some vagaries of the way the FMC system interacts with the payment processor; apparently I selected a suboptimal setting when setting it up. So if you’re one of those nine backers, or if you weren’t but you’d like to jump in there ex post facto, you can back the album here.

And finally, a reader had a question about Umberto Eco’s work and how it relates to conspiracy theory:

I have reread Foucault’s Pendulum and I have read The Name of the Rose and The Prague Cemetery. You said in your 2013 top ten list of books that “Perhaps my subscription to the conspiracy theory of history is one reason I rate Foucault’s Pendulum so highly, but I stand firmly by my high regard for Eco.” I have tried to get a more subtle read on Eco’s work rereading “FP” but It seems to me he is very much interested on demystifying these tropes, for example by constructing a plot in which the conspiracionist take the mad theories from three leftist editors very seriously and end up killing the main architect of the madness because the only way to salvage his hurt pride (the novel is very funny in the constant humillition of Belbo, specially the scenes in which Lorenza is involved) is to not reveal the secret: that there is no secret, it is all false.

In the “PC” something similar happens, where all the conspiracies of the late 19 century are pinned under a despicable guy who has no values but the love of money and will invent anything, including a Jewish conspiracy to take over the world. So Eco gives us a fictional account of the birth of a text, “The protocols of the elders of Sion”, that in the official history is considered to be a libel. Now I am sure these things don’t escape you, because you are much more smarter than me, but I still don’t see how his work vindicates your phrase I quoted. Is it just that you enjoy these themes treated in such a beautiful and sophisticated way, even though the author does not believe in them? Or is it the classic the message trascends the writter, and the story is more true than he seems to believe?

The reader seems to have a fundamental problem understanding the concept of a novel and its relation to the writer. Contra his assumptions, he has no idea what Eco actually thought about any of these things, which would be true of most halfway-decent authors, but is particularly true of an author who just happens to be a world expert on semiotics, signs, and symbols.

The idea that Eco is demystifying anything is absurd on its face. He loved myths, fables, and conspiracies. To look at his various explanations for them as attempts to reduce them to harmlessness in the service of the mainstream Narrative in which nothing happens for a reason and nobody accomplishes anything is to fundamentally miss the point. Eco was more akin to someone who loves puzzles and enjoys putting them together, which is why anyone else who loves puzzles will enjoy reading his book; moreover, let’s not forget the concept of blown cover as cover.

Being a world-famous public intellectual, Eco would have known better than anyone that there are secrets that cannot be safely revealed to everyone. Ergo, what better way to reveal them than by doing so in an innocuous manner that purports to make it clear that the secrets, such as they are, don’t even exist, especially given the inarguable evidence that they do, in fact exist. And this is precisely the sort of interpretation that one could not possibly rule out, given Eco’s very puckish sense of humor.

DISCUSS ON SG