Another intriguing excerpt from Castalia History’s forthcoming Studies On Napoleonic Warfare by Sir Charles Oman addresses the truth behind the history of the tactical conflict between the French column and the British line.

Every student who takes a serious interest in military history is aware that, in a general way, the victories of Wellington over his French adversaries were due to a skilful use of the two-deep British line against the massive column, which had become the regular formation for a French army acting on the offensive, during the later years of the great war that raged from 1792 till 1814. But I am not sure that the methods and limitations of Wellington’s system are fully appreciated. For it is not sufficient to lay down the general thesis that he found himself opposed by troops who invariably worked in columns, and that he beat those troops by the simple expedient of meeting them, front to front, with other troops who as invariably fought in the two-deep battle-line. The statement is true in a rough way, but needs explanation and modification.

The use of infantry in line was no invention of Wellington’s, nor is it a universal panacea for all the crises of war. Troops who are armed with missile weapons, and who hope to prevail in combat by the rapidity and accuracy of their shooting, must necessarily array themselves in an order of battle which permits as many men as possible to use their arms freely. This was as clear to Edward III at Crecy, or to Henry V at Agincourt, as to Wellington at Bussaco and Salamanca. A shooting-line must be made as thin as is consistent with solidity, since every soldier who is placed so far to the rear that he cannot see the object at which he is aiming represents a lost weapon, whether he be armed with bow, or with musket, or with rifle. Unaimed fire was even more fruitless in the days of short ranges than it is in the XXth century. And the general principles which guided an English general who wished to win by his archery in the Hundred Years War were much the same as those which prevail today.

The reason this topic is relevant today, more than 200 years later, is that rather like the period in the 17th century when the dispersed shooting line disappeared in favor of dense columns and the post-Civil War period when artillery and machine guns made it necessary to eliminate both line and column entirely, the battlefield is undergoing another period of tactical reconsideration, this time brought about by new drone and facial recognition technology.

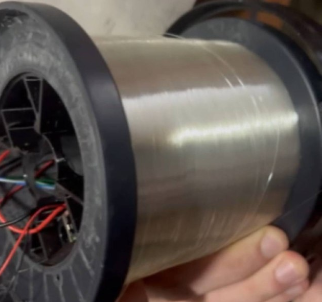

These developments may, in fact, render the battlefield itself obsolete. The Kalishnikov Zala Product 55 quadcopter not only carries an explosive charge, but as can be seen in the embedded image, spools out 6.7 miles of fiber-optic cable to render it immune to electronic jamming, making it all but unstoppable by anything except elite skeet shooters and anti-air laser defense systems.

Which is just another reason to stay safely inside at home reading the Castalia Library substack, which being entirely free, is not only educational, but an unbeatable value, in addition to keeping Library, Libraria, and History subscribers even more up to date than the monthly newsletter. And if you’re a parent, you might want to consider subscribing to the Junior Classics substack, which is presently wrapping up the final section of the pre-Devil Mouse version of The Beauty and the Beast.