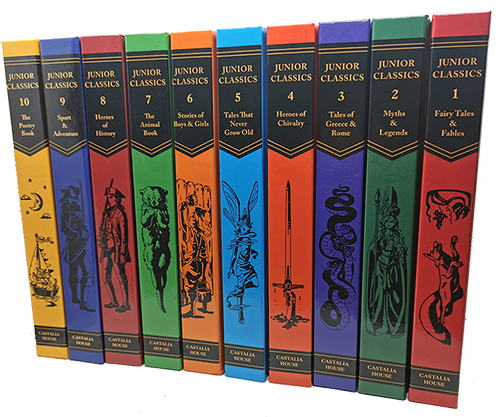

FYI: we’re rapidly approaching the last few hours of the Thanksgiving Junior Classics sale. The sets will still be available going forward at the following links, and via Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other booksellers, but the price will be the retail price $349.99 instead of the sale price of $249.99

And remember, if you’re having any trouble ordering from Arkhaven, please don’t hesitate to use NDM Express. They’re two entirely different systems, so if one doesn’t work, the other usually will.

HECTOR AND AJAX, from Tales of Greece and Rome

The Greeks went forward to the battle, as the waves that curl themselves and then dash upon the shore, throwing high the foam. In order they went after their chiefs; you had thought them dumb, so silent were they. But the Trojans were like a flock of ewes which wait to be milked, and bleat hearing the voice of their lambs, so confused a cry went out from their army, for there were men of many tongues gathered together. And on either side the gods urged them on, but chiefly Minerva the Greeks and Mars the sons of Troy. Then, as two streams in flood meet in some chasm, so the armies dashed together, shield on shield and spear on spear.

Now when Minerva saw that the Greeks were perishing by the hand of Hector and his companions, it grieved her sore. So she came down from the heights of Olympus, if happily she might help them. And Apollo met her and said, “Art thou come, Minerva, to help the Greeks whom thou lovest? Well, let us stay the battle for this day; hereafter they shall fight till the doom of Troy be accomplished.”

But Minerva answered, “How shall we stay it?”

And Apollo said, “We will set on Hector to challenge the bravest of the Greeks to fight with him, man to man.”

So they two put the matter into the mind of Helenus the seer. Then Helenus went near to Hector, “Listen to me, for I am thy brother. Cause the rest of the sons of Troy and of the Greeks to sit down, and do thou challenge the bravest of the Greeks to fight with thee, man to man. And be sure thou shalt not fall in the battle, for the will of the immortal gods is so.”

Then Hector greatly rejoiced, and passed to the front of the army, holding his spear by the middle, and kept back the sons of Troy, and King Agamemnon did likewise with his own people. Then Hector spake:

“Hear me, sons of Troy, and ye men of Greece. The covenant that we made one with another hath been broken, for Jupiter would have it so, purposing evil to both, till either you shall take our high-walled city or we shall conquer you by your ships. But let one of you who call yourselves champions of the Greeks come forth and fight with me, man to man. And let it be so that if he vanquish me he shall spoil me of my arms but give my body to my people, that they may burn it with fire, and if I vanquish him, I will spoil him of his arms but give his body to the Greeks, that they may bury him and raise a great mound above him by the broad salt river of Hellespont. And so men of after days shall see it, sailing by, and say, `This is the tomb of the bravest of the Greeks, whom Hector slew.’ So shall my name live forever.”

But all the Greeks kept silence, fearing to meet him in battle, but shamed to hold back. Then at last Menelaus leapt forward and spake, “Surely now ye are women and not men. Foul shame it were should there be no man to stand up against this Hector. Lo! I will fight with him my own self, for the issues of battle are with the immortal gods.”

So he spake in his rage rashly, courting death, for Hector was much stronger than he. Then King Agamemnon answered, “Nay, but this is folly, my brother. Seek not in thy anger to fight with one that is stronger than thou; for as for this Hector, even Achilles was loth to meet him. Sit thou down among thy comrades, and the Greeks will find some champion who shall fight with him.”

And Menelaus hearkened to his brother’s words, and sat down. Then Nestor rose in the midst and said, “Woe is me today for Greece! How would the old Peleus grieve to hear such a tale! Well I remember how he rejoiced when I told him of the house and lineage of all chieftains of the Greeks, and now he would hear that they cower before Hector, and are sore afraid when he calls them to the battle. Surely he would pray this day that he might die! O that I were such as I was in the old days, when the men of Pylos fought with the Arcadians! I, who was the youngest of all, stood forth, and Minerva gave me glory that day, for I slew their leader, though he was the strongest and tallest among the sons of men. Would that I were such today! Right soon would I meet this mighty Hector.”

Then rose up nine chiefs of fame. First of all, King Agamemnon, lord of many nations, and next to him Diomed, and Ajax the Greater and Ajax the Less, and then Idomeneus and Meriones, and Eurypylus, and Thoas, son of Andraemon, and the wise Ulysses.

Then Nestor said, “Let us cast lots who shall do battle with the mighty Hector.”

So they threw the lots into the helmet of King Agamemnon, a lot for each. And the people prayed, “Grant, ye gods, that the lot of Ajax the Greater may leap forth, or the lot of Diomed, or the lot of King Agamemnon.”

Then Nestor shook the lots in the helmet, and the one which they most wished leapt forth. For the herald took it through the ranks and showed it to the chiefs, but none knew it for his own till he came to where Ajax the Greater stood among his comrades. But Ajax had marked it with his mark, and put forth his hand for it, and claimed it, right glad at heart. On the ground by his feet he threw it, and said:

“Mine is the lot, my friends, and right glad I am, for I think that I shall prevail over the mighty Hector, but come, let me don my arms, and pray ye to Jupiter, but silently, lest the Trojans hear, or aloud, if ye will, for no fear have we. Not by force or craft shall any one vanquish me, for not such are the men whom Salamis breeds.”

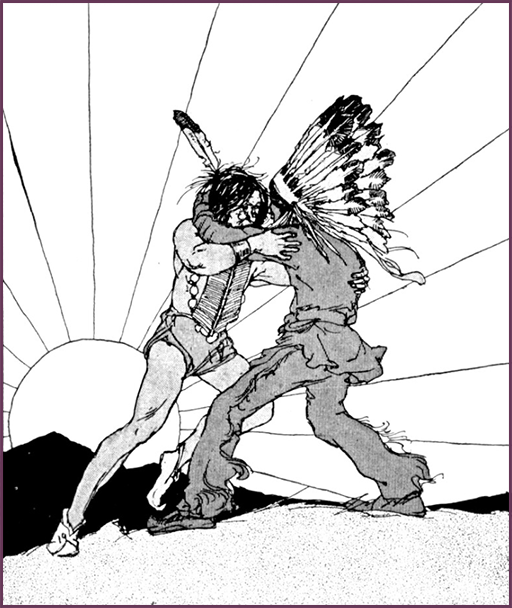

So he armed himself and moved forwards, smiling with grim face. With mighty strides he came, brandishing his long-shafted spear. The Greeks were glad to behold him, but the knees of the Trojans were loosened with fear and great Hector’s heart beat fast, but he trembled not, nor gave place, seeing that he had himself called him to battle. So Ajax came near, holding before the great shield, like a wall, which Tychius, best of craftsmen, had made for him. Seven folds of bull’s hide it had, and an eighth of bronze. Threateningly he spake:

“Now shalt thou know, Hector, what manner of men there are yet among our chiefs, though Achilles the lion-hearted is far away, sitting idly in his tent, in great wrath with King Agamemnon. Do thou, then, begin the battle.”

“Speak not to me, Jupiter-descended Ajax,” said Hector, “as though I were a woman or a child knowing nothing of war. Well I know all the arts of battle, to ply my shield this way and that, to guide my car through the tumult of steeds, and to stand fighting hand to hand. But I would not smite so stout a foe by stealth, but openly.”

As he spake he hurled his long-shafted spear, and smote the great shield on the rim of the eighth fold, that was of bronze. Through six folds it passed, but in the seventh it was stayed. Then Ajax hurled his spear, striking Hector’s shield. Through shield it passed and corslet, and cut the tunic close against the loin, but Hector shrank away and escaped the doom of death. Then, each with a fresh spear, they rushed together like lions or wild boars of the wood.

First Hector smote the middle of the shield of Ajax, but pierced it not, for the spear-point was bent back; then Ajax, with a great bound, drove his spear at Hector’s shield and pierced it, forcing him back, and grazing his neck so that the blood welled out. Yet did not Hector cease from the combat. He caught up a great stone from the ground, and hurled it at the boss of the sevenfold shield. Loud rang the bronze, but the shield broke not. Then Ajax took a stone heavier by far, and threw it with all his might. It broke the shield of Hector, and bore him backwards, so that he fell at length with his shield above him. But Apollo raised him up. Then did both draw their swords, but ere they could join in close battle the heralds came and held their scepters between them, and Idaeus, the herald of Troy, spake.

“Fight no more, my sons; Jupiter loves you both, and ye are both mighty warriors. That we all know right well. But now the night bids you cease, and it is well to heed its bidding.”

Then said Ajax, “Nay, Idaeus, but it is for Hector to speak, for he called the bravest of the Greeks to battle. And as he wills it, so will I.”

And Hector said, “O Ajax, the gods have given thee stature and strength and skill, nor is there any better warrior among the Greeks. Let us cease then from the battle; we may yet meet again, till the gods give the victory to me or thee. And now let us give gifts the one to the other, so that Trojans and Greeks may say—Hector and Ajax met in fierce fight and parted in friendship.”

So Hector gave to Ajax a silver-studded sword with the scabbard and the sword-belt, and Ajax gave to Hector a buckler splendid with purple. So they parted. Right glad were the sons of Troy when they saw Hector returning safe. Glad also were the Greeks, as they led Ajax rejoicing in his victory to King Agamemnon. Whereupon the king called the chiefs to banquet together, and bade slay an ox of five years old, and Ajax he honored most of all. When the feast was ended Nestor said:

“It were well that we should cease awhile from war and burn the dead, for many, in truth, are fallen. And we will build a great wall and dig a trench about it, and we will make wide gates that a chariot may pass through, so that our ships may be safe, if the sons of Troy should press us hard.”

But the next morning came a herald from Troy to the chiefs as they sat in council by the ship of King Agamemnon, and said:

“This is the word of Priam and the men of Troy; Paris will give back all the treasures of the fair Helen, and many more besides, but the fair Helen herself he will not give. But if this please you not, grant us a truce, that we may bury our dead.”

Then Diomed spake, “Nay, we will not take the fair Helen’s self, for a man may know even though he be a fool, that the doom of Troy is come.”

And King Agamemnon said, “Herald, thou hast heard the word of the Greeks, but as for the truce, be it as you will.”

So the next day they burnt their dead, and the Greeks made a wall with gates and dug a trench about it. And when it was finished, even at sunset, they made ready a meal, and lo! There came ships from Lemnos bringing wine, and Greeks bought thereof, some with bronze, and some with iron, and some with shields of ox hide. All night they feasted right joyously. The sons of Troy also feasted in their city. But the dreadful thunder rolled through the night, for Jupiter was counselling evil against them.

DISCUSS ON SG