It was just remarkable, with this evolutionary distance, that we should see such coherence in gene expression patterns. I was surprised how well everything lined up.

—Dr. Robert Waterston, co-senior author, Science (2025)

If one wanted to design an experiment to give natural selection the best possible chance of demonstrating its creative power, it would be hard to improve on the nematode worm.

Caenorhabditis elegans is about a millimeter long and consists of roughly 550 cells. It has a generation time of approximately 3.5 days. It produces hundreds of offspring per individual. Its populations are enormous. Its genome is compact—about 20,000 genes, comparable in number to ours but without the vast regulatory architecture that slows everything down in mammals. The worms experience significant selective pressure: most offspring die before reproducing, which means natural selection has plenty of raw material to work with. And critically, worms have essentially no generation overlap. When a new generation hatches, the old generation is dead or dying. Every generation represents a complete turnover of the gene pool. There is no drag, no cohort coexistence, no grandparents competing with grandchildren for resources.

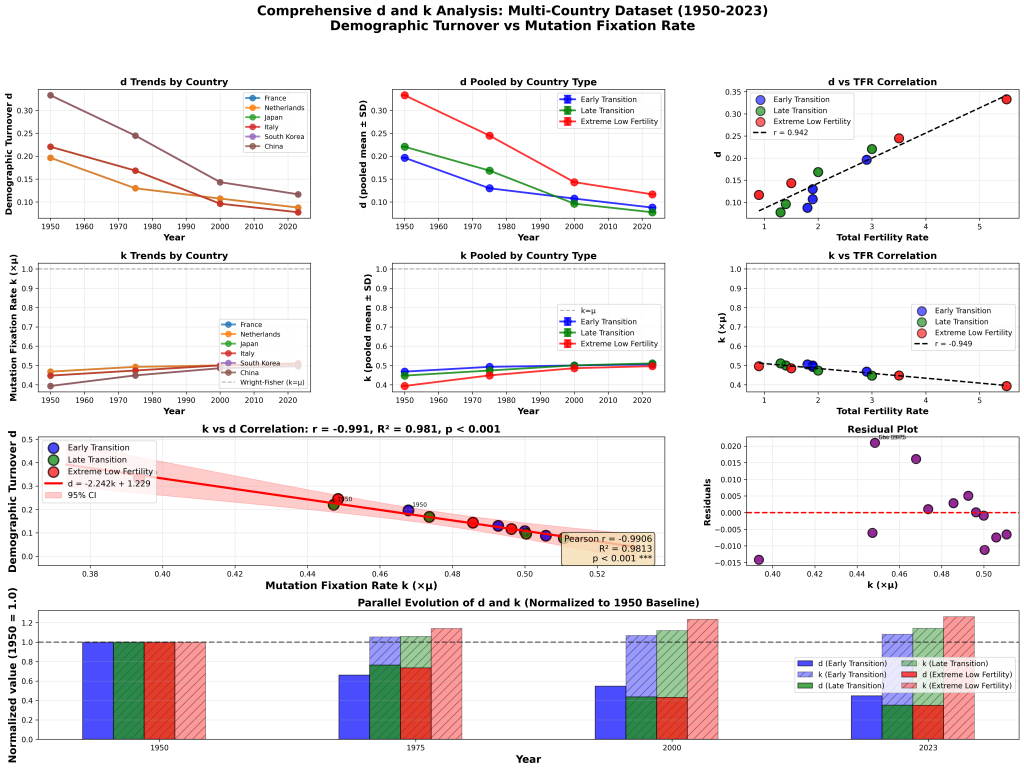

In the notation of the Bio-Cycle Fixation Model, the selective turnover coefficient for C. elegans is approximately d = 1.0. Compare that to humans, where we have shown d ≈ 0.45. The worm is running the evolutionary engine at full throttle. No brakes, no friction, no generational overlap gumming up the works.

Now consider the timescale. C. elegans and its sister species C. briggsae diverged from a common ancestor approximately 20 million years ago. At 3.5 days per generation, that is roughly two billion generations. To put that in perspective, the entire history of the human lineage since the putative chimp-human divergence—six to seven million years at 29 years per generation—amounts to something like 220,000 generations. The worms have had nearly ten thousand times as many generations to diverge. Ten thousand times.

Two billion generations, running the evolutionary engine at maximum speed, with enormous populations, high fecundity, complete generational turnover, and all the raw material that natural selection could ask for. If there were ever a case where the neo-Darwinian mechanism should produce spectacular results, this is it.

So what did it produce? Nothing.

In June 2025, a team led by Christopher Large and co-senior authors Robert Waterston, Junhyong Kim, and John Isaac Murray published a landmark study in Science comparing gene expression patterns in every cell type of C. elegans and C. briggsae throughout embryonic development. Using single-cell RNA sequencing, they tracked messenger RNA levels in individual cells from the 28-cell stage through to the formation of all major cell types—a process that takes about 12 hours in these organisms.

What they found is what Dr. Waterston described, with evident surprise, as “remarkable coherence.” Despite 20 million years and two billion generations of evolution, the two species retain nearly identical body plans with an almost one-to-one correspondence between cell types. The developmental program—when and where each gene turns on and off as the embryo develops—has been conserved to a degree that startled even the researchers.

Gene expression patterns in cells performing basic functions like muscle contraction and digestion were essentially unchanged between the two species. The regulatory choreography that builds a worm from a fertilized egg—which genes activate in which cells at which times—was so similar across 20 million years that the researchers could map one species’ cells directly onto the other’s.

Where divergence did occur, it was concentrated in specialized cell types involved in sensing and responding to the environment. Neuronal genes, the researchers noted, “seem to diverge more rapidly—perhaps because changes were needed to adapt to new environments.” But even this divergence was modest enough that Kim, one of the co-senior authors, noted the most surprising finding was not that some expression was conserved—the body plans are obviously similar, so that’s expected—but that “when there were changes, those changes appeared to have no effect on the body plan.”

Read that again. The changes that the mechanism did produce over two billion generations had no detectable effect on how the organism is built. The divergence was, as far as the researchers could determine, functionally trivial.

Murray, the study’s third senior author, offered the most revealing comment of all: “It’s hard to say whether any of the differences we observed were due to evolutionary adaptation or simply the result of genetic drift, where changes happen randomly.”

After two billion generations, the researchers cannot confidently identify a single adaptive change in gene expression. They cannot point to one cell type, one gene, one regulatory switch and say: natural selection did this. Everything they found is equally consistent with random noise.

Now, the standard response to findings like this is to invoke purifying selection, also known as stabilizing selection. The argument goes like this: most mutations are deleterious, so natural selection acts primarily to remove harmful changes rather than to accumulate beneficial ones. Gene expression patterns are conserved because any change to a broadly-expressed gene would disrupt too many downstream processes. The machinery is locked down precisely because it works, and selection fiercely punishes any attempt to modify it.

This is true. Purifying selection is real, well-documented, and no one disputes it. But invoking it as an explanation only deepens the problem for the neo-Darwinian account of speciation.

The theory of evolution by natural selection claims that the same mechanism, random mutation filtered by selection, both preserves existing adaptations and creates new ones. The worm data shows empirically what the constraint looks like. The vast majority of the genome is locked down. Expression patterns involving basic cellular functions are untouchable. The only genes free to diverge are those expressed in a few specialized cell types, and even those changes are so subtle that the researchers can’t distinguish them from genetic drift.

This is the genome’s evolvable fraction, and it is small. The regulatory architecture that controls development, the transcription factor binding sites, the enhancer networks, the chromatin structure that determines which genes are accessible in which cells, is so deeply entrenched that two billion generations of nematode reproduction cannot budge it.

And here’s the question no one asked: how did that regulatory architecture get there in the first place?

If the current architecture is so tightly constrained that it resists modification across two billion generations, then building it in the first place required an even more extraordinary series of changes. Every transcription factor binding site had to be fixed. Every enhancer had to be positioned. Every element of the chromatin landscape that determines which genes are expressed in which cell types had to be established through sequential substitutions. This is what we call the shadow accounting problem. The very architecture now being invoked to explain why the worm hasn’t changed is itself a product that requires explanation under the same model. The escape hatch invokes a mechanism whose existence demands an even larger prior expenditure of the same mechanism—an expenditure that the breeding reality principle tells us was itself problematic.

Let us be precise about the scale of the failure. The MITTENS analysis, as published in Probability Zero, establishes that the neo-Darwinian mechanism of natural selection faces multi-order-of-magnitude shortfalls when asked to account for the fixed genetic differences between closely related species. The worm study provides an independent empirical check on this conclusion from the opposite direction.

Instead of asking “can the mechanism produce the required divergence in the available time?” and discovering that it cannot, the worm study asks “what does the mechanism actually produce when given enormous amounts of time under ideal conditions?” and discovers that the answer is exactly what MITTENS proves: essentially nothing.

Two billion generations with every parameter set to maximize the rate of adaptive change, with short generation times, high fecundity, large populations, complete generational turnover, and a compact genome, nevertheless produced two organisms so similar that researchers can map their cells one-to-one. The divergence that did occur was concentrated in a few specialized cell types and could not be confidently attributed to adaptation.

Now scale this down to the conditions that supposedly produced speciation in large mammals. A large mammal has a generation time of 10 to 20 years. Its fecundity is low, with a few offspring per lifetime instead of hundreds. Its effective population size is small. Its generation overlap is substantial (d ≈ 0.45, meaning that less than half the gene pool turns over per generation). Its genome is vastly larger and more complex, with regulatory architecture orders of magnitude more elaborate than a nematode’s.

The number of generations available for speciation in large mammals is measured in the low hundreds of thousands. The worms had two billion and produced nothing visible. On what basis should we believe that a mechanism running at a fraction of the speed, with a fraction of the population size, a fraction of the fecundity, a fraction of the generational turnover, and orders of magnitude more regulatory complexity to navigate, can accomplish what the worms could not?

The question answers itself.

“The worms are under strong stabilizing selection. Other lineages face different selective pressures that drive divergence.”

No one disputes that stabilizing selection explains the stasis. The problem is what happens when you look at the fraction that isn’t stabilized. Two billion generations of mutation, selection, and drift operating on the unconstrained portion of the genome produced changes that (a) affected only specialized cell types, (b) didn’t alter the body plan, and (c) couldn’t be distinguished from drift. If the creative power of natural selection operating on the evolvable fraction of the genome is this feeble under ideal conditions, it does not become more powerful when you make conditions worse.

“Worms are simple organisms. Complex organisms have more regulatory flexibility.”

This gets the argument backward. Greater complexity means more regulatory interdependence, which means more constraint, not less. A change to a broadly-expressed gene in an organism with 200 cell types is more dangerous than a change to a broadly-expressed gene in an organism with 30 cell types, because there are more downstream processes to disrupt. The more complex the organism, the smaller the evolvable fraction of the genome becomes relative to the locked-down fraction.

“Twenty million years is a short time in evolutionary terms.”

It is 20 million years in clock time but two billion generations in evolutionary time. The relevant metric for evolution is not years but generations, because selection operates once per generation. Two billion generations for a nematode is equivalent, in terms of opportunities for selection to act, to 58 billion years of human evolution at 29 years per generation. That’s more than four times the age of the universe. If the mechanism can’t produce meaningful divergence in the equivalent of four universe-lifetimes, the mechanism obviously doesn’t function at all.

“The study only looked at gene expression, not genetic sequence. There could be extensive sequence divergence not reflected in expression.”

There is sequence divergence, and it’s well-documented. C. elegans and C. briggsae differ at roughly 60-80% of synonymous sites and show substantial divergence at non-synonymous sites as well. The point is that this sequence divergence has not produced meaningful functional divergence. The genes have changed, but what they do and when they do it has remained largely the same. Sequence divergence without functional divergence is exactly what you’d expect from neutral drift operating on a tightly constrained system—and it is exactly the opposite of what you’d expect if natural selection were the creative engine the theory claims it to be.

The Science study is good science. The researchers accomplished something genuinely unprecedented: a cell-by-cell comparison of gene expression between two species across the entire course of embryonic development. The technical accomplishment is significant, and the evidence it produced is highly valuable.

But the data is reaching a conclusion that the researchers are not eager to draw. Two billion generations of evolution, operating under conditions more favorable than any large animal will ever experience, failed to produce any meaningful or functional divergence between two species. The mechanism ran at full speed for an incomprehensible span of time, and the result was the same worm.

This is not a philosophical objection to evolution. It is not an argument from personal incredulity or religious conviction. It is the straightforward empirical observation that the proposed mechanism, given every possible advantage, does not produce the results attributed to it. The creative power of natural selection, when measured rather than assumed, turns out to be approximately zero.

Two billion generations of nothing. A worm frozen in time. That’s what the data shows. And that’s exactly what Probability Zero predicted.