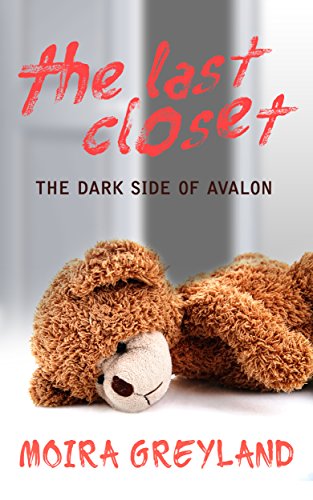

Marion Zimmer Bradley was a bestselling science fiction author, a feminist icon, and was awarded the World Fantasy Award for lifetime achievement. She was best known for the Arthurian fiction novel THE MISTS OF AVALON and for her very popular Darkover series.

She was also a monster.

THE LAST CLOSET: The Dark Side of Avalon is a brutal tale of a harrowing childhood. It is the true story of predatory adults preying on the innocence of children without shame, guilt, or remorse. It is an eyewitness account of how high-minded utopian intellectuals, unchecked by law, tradition, religion, or morality, can create a literal Hell on Earth.

THE LAST CLOSET is also an inspiring story of survival. It is a powerful testimony to courage, to hope, and to faith. It is the story of Moira Greyland, the only daughter of Marion Zimmer Bradley and convicted child molester Walter Breen, told in her own words.

In case you’ve been wondering why I haven’t been doing Darkstreams, finishing the extended edition of A Sea of Skulls, or wrapping up the first Voxiversity, well, this is why. To paraphrase the author, this is a difficult book to read, it was almost impossible to write, and it wasn’t exactly easy to edit or proofread either, which is why I am very grateful to the assistant editor and the two proofreaders for their invaluable assistance in this regard.

Moira asked me to write the foreword to The Last Closet. I will have more to add later, but for now, it will suffice as my public comment on the subject.

I read four or five of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s books in high school. I started with The Heritage of Hastur, then read two or three more Darkover novels that caught my eye in the Arden Hills library. While I didn’t find them sufficiently entertaining to continue with the series, they were just interesting enough to inspire me to pick up a trade paperback of The Mists of Avalon not long after it was published by Del Rey in 1984. As it happens, I still have that much-ballyhooed monstrosity, its long-untouched pages now yellowing on a dusty bookshelf in the attic.

The Mists of Avalon was a massive 876-page bestseller heavily marketed as a feminist take on Camelot and the legends of King Arthur, and was critically hailed for being very different than the usual retellings of the classic tale. It was different, and in some ways, with its grim darkness and overt sexuality, The Mists of Avalon might even be considered a predecessor of sorts to George R.R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones. I found it to be too much of a soap opera myself, and certainly not a patch on Chrétien de Troyes, Thomas Malory, or even T.H. White, although there were a few salacious sections that did serve to liven up the book considerably.

But even as a red-blooded young man, some of those sections struck me as perhaps a little too salacious. While I can’t say that I had any inkling of what the author’s habits or home life were at the time, I did detect a slight sense of what I can only describe as a wrongness from the book. Arthur didn’t love Guinevere, but was pining away for his half-sister? Sir Lancelot was not only Galahad, but also Arthur’s bisexual cousin? Instead of being a tragic love triangle, Arthur, Launcelot, and Guinevere were a swinging threesome? And Mordred was not only Arthur’s son, but the product of incest knowingly orchestrated by Merlin for pagan purposes to boot?

Yeah, that’s not hot. That’s just weird and more than a little grotesque.

I don’t recall if I ever actually finished the novel or not, but I know I didn’t bother reading any of its many sequels. I felt that I had given this vaunted feminist author a fair shake and delved as deeply into Ms. Bradley’s strange psyche as I wished to go, little knowing that what I dismissed as freakish feminist literary antics were merely scratching the surface on what was actually an intergenerational psychosexual horror show.

Three decades later, despite being a science fiction author and editor myself, I found myself increasingly at odds with the creepy little community known as SF fandom, which can best be described as the cantina crowd from Star Wars, only depressed, overweight, and sexually confused. At the same time, I was also becoming increasingly aware of a wrongness that emanated from that community like a faint, but unmistakably foul odor.

There were rumors about the real reason behind science fiction grandmaster Arthur C. Clarke’s bizarre relocation from southern California to Sri Lanka. There was the arrest of David Asimov, son of science fiction legend Isaac Asimov, for the possession of the largest stash of child pornography the police had ever seen. There were the public defenses offered by many science fiction authors on behalf of the SFWA member and convicted child molester Ed Kramer. There was the naming of NAMBLA enthusiast and homo-horrorporn author Samuel Delaney as SFWA’s 2013 Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master.

And then, of course, there was the historical Breendoggle, a fifty-year-old debate among science-fiction fandom concerning whether a child molester, Walter Breen, should have been permitted to attend the science-fiction convention known as Pacificon II or not. Believe it or not, the greater part of fandom at the time was outraged by the committee’s sensible decision to deny Breen permission to attend the 1964 convention; science-fiction fandom continued to cover for the notorious pedophile even after his death in 1993. In “Conspiracy of silence: fandom and Marion Zimmer Bradley”, Martin Wisse wrote:

Why indeed did it take until MZB was dead for her covering for convicted abuser Walter Breen to become public knowledge and not just whispered amongst in the know fans. Why in fact was Breen allowed to remain in fandom, being able to groom new victims? Breen after all was first convicted in 1954, yet could carry out his grooming almost unhindered at sf cons until the late nineties. And when the 1964 Worldcon did ban him, a large part of fandom got very upset at them for doing so.

The fact that fandom had been covering for pedophiles for decades was deeply troubling. And yet, we would soon learn that this wrongness in science fiction ran even deeper than the most cynical critics suspected.

On June 3, 2014, a writer named Deirdre Saorse Moen put up a post protesting the decision of Tor Books to posthumously honor Tor author and World Fantasy Award-winner Marion Zimmer Bradley, on the basis of Bradley’s 1998 testimony given in a legal deposition about her late husband. When Moen was called out by Bradley fans for supposedly misrepresenting Bradley, she reached out to someone she correctly felt would know the truth about the feminist icon: Moira Greyland, the daughter of Marion Zimmer Bradley and Walter Breen.

Little did Moen know how dark the truth about the famous award-winning feminist was. For when Moira responded a few days later, she confirmed Moen’s statement about Marion Zimmer Bradley knowing all about her pedophile husband’s behavior. However, Moira also added that her famous mother had been a child molester as well, and that in fact, Bradley had been far more violently abusive to both her and her brother than Breen!

I will not say more about the harrowing subject of this book because it is the author’s story to tell, not mine. But I will take this opportunity to say something about the author, whom I have come to admire for her courage, for her faith, and most of all, for her ability to survive an unthinkably brutal upbringing with both her sanity and her sense of humor intact.

Moira does not wallow in her victimhood. Nor does she paint her victimizers as soulless devils, indeed, her empathy for those who wronged her so deeply is more than astonishing, it is humbling. Her strength of character, her integrity, and her faith in a God she was raised to believe did not exist are almost inexplicable, particularly in an age where adult college students cannot face unintended microaggressions without the support of their university administrations, the campus police, and physician-prescribed pharmaceuticals.

Her story is more than a triumph of the human spirit, more than a tale of survival, and more than a devastating indictment of a seriously depraved community. It is an inspiration to everyone, particularly for anyone who has ever been subjected to abuse or ill-treatment as a child.

Moira’s message is clear: they can hurt you, they can harm you, and they can leave you with scars that last a lifetime, but they cannot touch your soul. Their sins are not your sins and their shame is not your shame. And there is a light that is always waiting to heal those who summon the strength to walk out of the last closet and turn their back on the darkness inside it.

UPDATE: Thank you for your strong support for the author.

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #392 Paid in Kindle Store

#1 in Books > Self-Help > Abuse

#1 in Kindle Store > Counseling & Psychology > Mental Health > Sexual Abuse

#1 in Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Biographies & Memoirs > Women