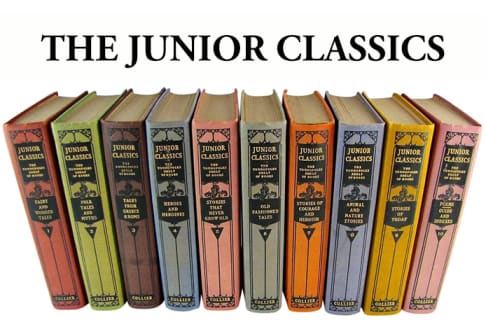

This is the sort of story that was published in the 1918 edition, systematically excised from the later editions, and is being brought back in the 2020 edition of the Junior Classics. Because a people who lose their stories soon lose their selves and become a demoralized people who lose their nation.

THE STORY OF KING ARTHUR

This great treasure-house of stories is to the English race what the stories of Ulysses and Aeneas were to the Greeks and Latins, a national inheritance of which they should be, and are, proud.

The high nobility, dauntless courage and gentle humility of Arthur and his knights have had a great effect in moulding the character of English peoples, since none of us can help trying to imitate what he admires and loves most.

As a series of pictures of life in the Middle Ages the stories are of the greatest value. The geography is confused, as it is in the Iliad and the Odyssey, and facts are sometimes mixed up with magic, but modern critics believe there was a real Arthur, who lived about the year 500 A.D.

OF ARTHUR’S BIRTH AND HOW HE BECAME KING

Long years ago, there ruled over Britain a king called Uther Pendragon. A mighty prince was he, and feared by all men; yet when he sought the love of the fair Igraine of Cornwall, she would have naught to do with him, so that, from grief and disappointment, Uther fell sick, and at last seemed like to die.

Now in those days, there lived a famous magician named Merlin, so powerful that he could change his form at will, or even make himself invisible; nor was there any place so remote that he could not reach it at once, merely by wishing himself there. One day, suddenly he stood at Uther’s bedside, and said: “Sir king, I know thy grief, and am ready to help thee. Only promise to give me, at his birth, the son that shall be born to thee, and thou shalt have thy heart’s desire.” To this the king agreed joyfully, and Merlin kept his word: for he gave Uther the form of one whom Igraine had loved dearly, and so she took him willingly for her husband.

When the time had come that a child should be born to the king and queen, Merlin appeared before Uther to remind him of his promise; and Uther swore it should be as he had said. Three days later, a prince was born, and, with pomp and ceremony, was christened by the name of Arthur; but immediately thereafter, the king commanded that the child should be carried to the postern-gate, there to be given to the old man who would be found waiting without.

Not long after, Uther fell sick, and he knew that his end was come; so, by Merlin’s advice, he called together his knights and barons, and said to them: “My death draws near. I charge you, therefore, that ye obey my son even as ye have obeyed me; and my curse upon him if he claim not the crown when he is a man grown.” Then the king turned his face to the wall and died.

Scarcely was Uther laid in his grave before disputes arose. Few of the nobles had seen Arthur or even heard of him, and not one of them would have been willing to be ruled by a child; rather, each thought himself fitted to be king, and, strengthening his own castle, made war on his neighbors until confusion alone was supreme, and the poor groaned because there was none to help them.

Now when Merlin carried away Arthur—for Merlin was the old man who had stood at the postern-gate—he had known all that would happen, and had taken the child to keep him safe from the fierce barons until he should be of age to rule wisely and well, and perform all the wonders prophesied of him. He gave the child to the care of the good knight Sir Ector to bring up with his son Kay, but revealed not to him that it was the son of Uther Pendragon that was given into his charge.

At last, when years had passed and Arthur was grown a tall youth well skilled in knightly exercises, Merlin went to the Archbishop of Canterbury and advised him that he should call together at Christmas-time all the chief men of the realm to the great cathedral in London; “for,” said Merlin, “there shall be seen a great marvel by which it shall be made clear to all men who is the lawful king of this land.” The archbishop did as Merlin counselled. Under pain of a fearful curse, he bade the barons and knights come to London to keep the feast, and to pray heaven to send peace to the realm.

The people hastened to obey the archbishop’s commands, and, from all sides, barons and knights came riding in to keep the birth-feast of Our Lord. And when they had prayed, and were coming forth from the cathedral they saw a strange sight. There, in the open space before the church, stood, on a great stone, an anvil thrust through with a sword; and on the stone were written these words: “Whoso can draw forth this sword is rightful King of Britain born.”

At once there were fierce quarrels, each man clamoring to be the first to try his fortune, none doubting his success. Then the archbishop decreed that each should make the venture in turn, from the greatest baron to the least knight; and each in turn, having put forth his utmost strength, failed to move the sword one inch, and drew back ashamed. So the archbishop dismissed the company, and having appointed guards to watch over the stone, sent messengers through all the land to give word of great jousts to be held in London at Easter, when each knight could give proof of his skill and courage, and try whether the adventure of the sword was for him.

Among those who rode to London at Easter was the good Sir Ector, and with him his son, Sir Kay, newly made a knight, and the young Arthur. When the morning came that the jousts should begin, Sir Kay and Arthur mounted their horses and set out for the lists; but before they reached the field, Kay looked and saw that he had left his sword behind. Immediately Arthur turned back to fetch it for him, only to find the house fast shut, for all were gone to view the tournament. Sore vexed was Arthur, fearing lest his brother Kay should lose his chance of gaining glory, till, of a sudden, he bethought him of the sword in the great anvil before the cathedral. Thither he rode with all speed, and the guards having deserted their post to view the tournament, there was none to forbid him the adventure. He leaped from his horse, seized the hilt, and instantly drew forth the sword as easily as from a scabbard; then, mounting his horse and thinking no marvel of what he had done, he rode after his brother and handed him the weapon.

When Kay looked at it, he saw at once that it was the wondrous sword from the stone. In great joy he sought his father, and showing it to him, said: “Then must I be King of Britain.” But Sir Ector bade him say how he came by the sword, and when Sir Kay told how Arthur had brought it to him, Sir Ector bent his knee to the boy, and said: “Sir, I perceive that ye are my king, and here I tender you my homage;” and Kay did as his father. Then the three sought the archbishop, to whom they related all that had happened; and he, much marvelling, called the people together to the great stone, and bade Arthur thrust back the sword and draw it forth again in the presence of all, which he did with ease. But an angry murmur arose from the barons, who cried that what a boy could do, a man could do; so, at the archbishop’s word, the sword was put back, and each man, whether baron or knight, tried in his turn to draw it forth, and failed. Then, for the third time, Arthur drew forth the sword. Immediately there arose from the people a great shout: “Arthur is King! Arthur is King! We will have no King but Arthur;” and, though the great barons scowled and threatened, they fell on their knees before him while the archbishop placed the crown upon his head, and swore to obey him faithfully as their lord and sovereign.

Thus Arthur was made King; and to all he did justice, righting wrongs and giving to all their dues. Nor was he forgetful of those that had been his friends; for Kay, whom he loved as a brother, he made seneschal and chief of his household, and to Sir Ector, his foster father, he gave broad lands.